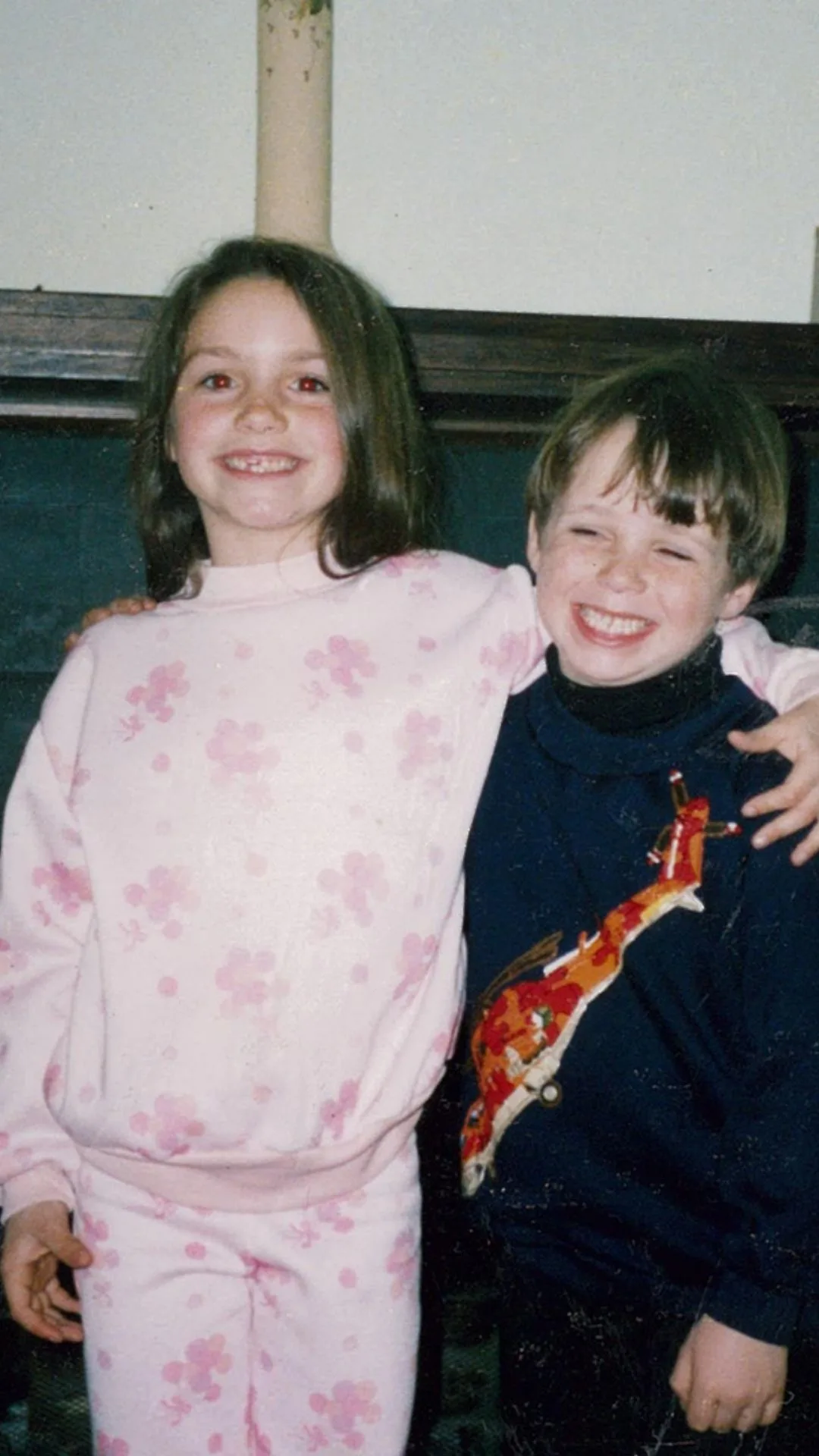

Some of Loren O’Keeffe’s favourite memories with her younger brother, Dan, are from spending long days together during endless school holidays. There was the time they decided to recreate a treasured blue milkshake they’d binged on during family summer vacations in Victoria’s Lorne.

The siblings mixed blue cordial, milk and ice-cream into the milkshake maker, and promptly gagged at the taste, throwing the failed experiment down the sink. There was the time they were obsessed with playing Nintendo, devoting hours to competing against each other in Mario Kart and Legend of Zelda battles.

There was the time Loren would watch her daredevil brother come flying down the hill on his roller blades, launching through the air off the ramp he built with the neighbourhood kids, twisting and twirling in mid-air. “He was just fearless,” Loren recalls fondly.

“I enjoyed watching him be a really talented skater. I’d see him down at the proper big skate ramps and the kids he was hanging out with were a few years older than him but he was doing tricks that they couldn’t. Not to show off, just to have a go. He was really bold and brave, but modest, and I was always so proud to be his big sister.”

With only two-and-a-half years between them, their close bond continued into adulthood. Dan opened up to Loren about his struggles with depression and anxiety, leaning on her for support. He spent a lot of time on his mental health, seeing a psychologist and learning about Buddhism.

He travelled the world and maintained a healthy lifestyle, going on to run a successful Brazilian jiujitsu academy in Melbourne, where he lived with his girlfriend of three years. At just 24, he seemingly had his whole life ahead of him.

But on an ordinary morning on July 15, 2011, Dan disappeared.

He had been staying at Geelong with his parents, Des and Lori, for a few nights and was due to meet up with Loren in two days for a fun run they had been training for. There was no indication beforehand that anything was amiss.

“He was still behaving and conversing normally and I had no reason to doubt I’d be seeing him that Sunday morning for the run,” says Loren. In movies and on television, when someone goes missing there is always a keen-eyed, work-addicted detective team whose singular purpose is to find the missing person. But Loren soon found out real life was nowhere close to what was depicted on the screen.

Resources and experience levels differ from station to station and from state to state. It took the Victorian police three days to come to her parents’ house to get photos of Dan, and even then it was only because the media had started reporting on it.

“When he was first reported missing, the police said, ‘Oh, well, he’s 24. He’s probably just blowing off some steam. He’ll be back in a couple of days.’

But we knew that wasn’t like Dan. It was completely out of character,” says Loren. “We felt as if we had to try to convince police that this was serious, and trying to convince them to care when you’re in a really distressed state, you’re not thinking clearly, you’re not sleeping, you’re not eating … It’s really devastating to feel that you need to prove your loved one is worthy of attention, to beg them to do the job you think that they’re supposed to do.”

Since Dan’s disappearance wasn’t considered suspicious, the police did not conduct a search. Instead, that was left in the hands of the family.

“I was madly running around Geelong, asking people if they’d seen Dan,” recalls Loren. “It was a really traumatic time. I asked the police what to do and they said, ‘Do whatever you feel like you need to do,’ which isn’t helpful.”

In the 14 years since, Loren says she’d like to think improvements have been made. “Victoria Police do seem to allocate some resources to non-suspicious cases now, which is good. But it still seems ad-hoc and not enough has changed,” she says. “It’s a complex space, and 85 per cent of cases relate to mental health, so we do really need to reframe missing persons as a community issue and a public health issue, rather than just lumping it on the police. Unless there’s a crime involved or a risk to the community, it’s kind of outside their remit because their primary function is to protect the community and respond to crime.”

If the O’Keeffe family felt let down by the police, their spirits were bolstered by the outpouring of love and support from the public. A Facebook page set up to find Dan amassed 10,000 followers in that first year alone.

By the fourth year it would have 70,000 followers. Posters of Dan’s smiling, handsome face were plastered in local cafes and workplaces and on bumper stickers. Hordes of strangers turned up when the family organised a search of the area surrounding their Geelong home. But the biggest effect was having people contacting them to say that seeing the impact of Dan’s disappearance on the family had prompted them to seek help for their own mental health, instead of going missing themselves.

“To know that our awareness was actually preventative, sparing other families our same fate, was a massive silver lining – completely unforeseen,” says Loren. “It’s still one of the biggest things for us to have taken out of this whole experience.”

In Australia, more than half of the missing person reports received by police each year relate to people aged between 13 and 17. There are about 2700 long-term missing people, defined as those missing for more than three months.

Although there have been no major changes in the number of missing persons reported in the past few years, the annual figure was about 30,000 back in 2011 and is about 57,000 today, so the numbers have almost doubled in less than 15 years.

While a completely centralised register of missing persons across Australia does not exist, the National Missing Persons Coordination Centre, a non-operational arm of the Australian Federal Police (AFP), facilitates national coordination and information sharing between states and territories.

More than 99 per cent of missing persons reports are resolved (meaning the person is located), and typically within a short period of time.

Dr Sarah Wayland, a professor of social work at CQU Sydney, who has worked in the missing persons sector for the past 21 years, says it is rare for returned people to voice their experience publicly. “This speaks to a few issues: shame and stigma about going missing, wanting to protect their privacy, especially if media outlets have previously shared their image during the time of searching, as well as not wanting to upset their family [by reminding] them of the time they were absent,” she says.

The disappearance of Tony Jones while backpacking in 1982 was the catalyst for the establishment of National Missing Persons Week (NMPW) in Australia in 1988 by the Jones family. Held annually during the first week of August, this year’s theme is Forever Loved, with a focus on acknowledging the experiences of families of missing persons.

“National Missing Persons Week raises awareness by sharing profiles of missing persons and appeals to the public for any information that could help locate them, reminding the public that even the smallest piece of information can be crucial in solving these cases,” AFP commander Joanne Cameron tells marie claire. “NMPW also serves as a reminder of the impact on families and communities that the disappearance of a loved one leaves. The uncertainty and pain of not knowing what happened can be overwhelming.”

As the days turned into weeks, weeks into months, and months into years, Loren and her family lived with this uncertainty and pain.

“That heightened awareness to every clue, idea, social media comment or even news about another missing person being located can be all-consuming,” says Wayland. “This is the lived experience of an ambiguous or unresolved loss, a feeling of not knowing, and unending pain that shapes each hour of each day. We know from research that the space between hopefulness and hopelessness is a constant tension.

Families of missing people feel that they are living a post-traumatic stress response. The trauma is both the person’s disappearance and the information that is known, as well as the imagined trauma of what they have gone through. Families tell me they would not wish this type of pain on their worst enemy.”

At first, the non-stop liaison with the public, media and police kept Loren going. Moreover, there was the hope that through each of those interactions, a resolution would soon come. A year later, while feeling completely demoralised by the failed efforts to find Dan, she started the charity Missing Persons Advocacy Network, now The Missed Foundation, which provides practical and emotional support to families just like hers. “Once I started the charity, I had a sense of purpose and meaning,” she recalls. “I really needed that to stay alive for all those years of the unending not-knowing. And it is still what gets me out of bed each day.”

In 2016, nearly five years after Dan went missing, he was found in an underground, hidden space beneath the family’s Geelong home. He had died by suicide. “I was crushed,” Loren says of finding out about Dan’s death.

“Even if a family of a long-term missing person does get resolution, you never get all the answers. And ambiguous loss stays with you forever. There is, of course, a sense of relief in being able to locate them. But when they’re found deceased, it’s a whole new layer of grief, with the obliteration of hope and the devastation of bereavement. Closure is a ridiculous concept people like to use to avoid the messiness of grief.”

Yet Loren is reminded every day how fortunate her family is to have a resolution, despite the devastation of losing Dan. “We do our best to live with positivity in his honour, and I am especially grateful to have found purpose through the work we do in his memory,” she says.

“We carry our grief, and it’s heavy, but I’m always conscious of how easily we could have been a family stuck with the unending not-knowing for decades or even, most tragically, the rest of our lives. We are grateful for that and for the 24 years we got to have Dan.”

Visit The Missed Foundation at missed.org.au for support. You can also call Lifeline for help anytime on 13 11 14 or visit lifeline.org.au. You do not have to wait 24 hours to report a person missing. If you have concerns for someone’s safety and welfare and their location is unknown, you can file a missing person report at your local police station.