What do you think of the state of feminism today?” It was a question I threw out to 10 prominent Australian women while researching this piece, keen to glean their insights on how the women’s movement was progressing and regressing.

I wanted to hear their thoughts on tradwives and femcels, on spicy Sabrina Carpenter album covers and dystopian abortion bans, but I received few replies. The silence in my inbox was deafening.

Which was surprising, because these were the kinds of women – activists, authors and social commentators – usually eager to share their big opinions. Perhaps, I resolved, it was a reflection of the load women are carrying in 2025, of their 720 unread emails, circus-worthy juggling performances and limited bandwidth to dive into another debate.

Had I posed the same question a decade ago, I’m confident I would have been inundated with responses. Back then, feminism was the word on everybody’s lips.

Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk “We Should All Be Feminists” had been watched by millions, its message of inclusion so powerful that every 16-year-old in Sweden was given a copy of her book of the same name.

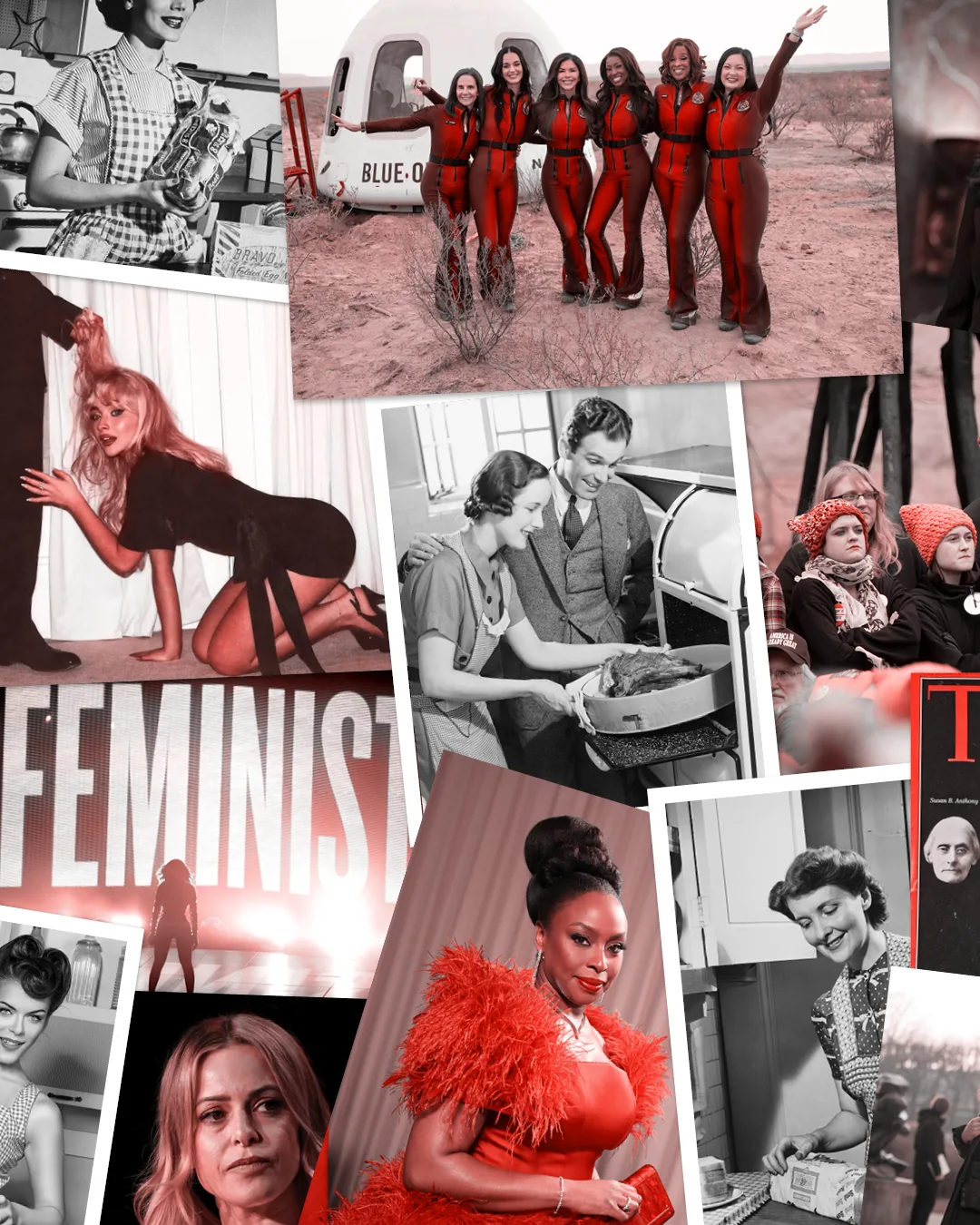

Beyoncé sampled the rousing speech on her track “Flawless” and performed it at the VMAs in front of a giant, lit-up FEMINIST sign.

“The next time a man asks me what Beyoncé has done for feminism, I will sit him in a chair and make him watch this performance for 24 hours,” was the overriding consensus on Twitter, back before Elon Musk turned the platform into a misogynistic cesspit.

Christian Dior would soon name Maria Grazia Chiuri as creative director, the first woman to helm the fashion house, and send slogan T-shirts down the runway declaring “The Future is Female”.

“Feminism – the F-word – is simultaneously simple to define yet loaded and complex.”

Corporate capitalism leaned in too, as per Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s directive to women to crack their own glass ceilings, while Nasty Gal founder Sophia Amoruso ushered in #girlboss culture and the millennial-pink-tinted promise of female ambition.

Feminism was everywhere – yes, heavily commercialised and often doused in gloss and glamour – but its presence was all-pervasive, a sign that the women’s movement was powerful and important, a cause and collective you wanted to be a part of.

Feminism – the F-word – is simultaneously simple to define yet loaded and complex. At its core, it’s about achieving equal rights for women and men, or, as feminist thinker bell hooks wrote in 1984, “Feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.” In Western society, the movement has risen in waves, the first of which crashed through in the mid-19th-century demanding women’s suffrage.

Second-wave feminism fought for reproductive rights, workplace equality and liberation from rigid domestic roles, while the third wave was angrier and more self-aware, focused on intersectionality and sex positivity.

The fourth wave kicked off around 2013, fuelled by the internet and online mobilisation that saw millions of people march to protest the pussy-grabbing US president Trump in January 2017, and to support survivors of sexual abuse in the #MeToo groundswell later that year.

The vibe has since shifted so dramatically you may be suffering from whiplash. Leaning in was superseded by leaning out – the former overlooked structural barriers and was leading more women to burnout than the boardroom – and #girlboss culture was cancelled for being fake-woke.

In its place came tradwives, a rising subculture that celebrates a return to traditional gender roles, female domesticity and shirred milkmaid dresses. At a conservative women’s event in Dallas, Texas, in June, attendees wore pins saying, “My favorite season is the fall of feminism”, while a MAGA/MAHA influencer preached, “Less burnout, more babies, less feminism, more femininity.”

Meanwhile, the closest we’ve come to celebrity-fronted “feminism” in 2025 was the Blue Origin NS-31 space stunt that saw Jeff Bezos’ band of blow-dried women “putting the ass in astronaut”, to quote Katy Perry.

The pop star was a curious inclusion in the all-female crew, given she repudiated feminism in the early 2010s, eventually conceding: “I used to not really understand what that word meant, and now that I do, it just means that I love myself as a female and I also love men.” So, she still doesn’t understand what it means.

More significantly, despite the global uprising for women in the late 2010s, the overturning of Roe v Wade in 2022 ended decades of federal protection over reproductive freedom in America. At the time of writing, 20 US states have banned abortion or restricted parameters around the procedure, with far-right and populist politicians around the world attempting to do the same. “Are people giving up on feminism in 2025?” pondered an SBS think piece in March.

It’s a valid question, given that a decade of A-list advocates and viral rallies haven’t translated into political, social or economic equity. Australian women earn on average $28,425 less than their male colleagues (that’s 78c earned to a man’s dollar), and hold just one in 12 CEO positions in the ASX300. We bear a disproportionate share of unpaid care and have 25 per cent less in our superannuation accounts, all while rates of gender-based violence rise.

According to a survey by market research firm Ipsos, 43 per cent of Australians (51 per cent of men and 35 per cent of women) believe that “when it comes to giving women equal rights with men, things have gone far enough in my country”.

In 2019, only 31 per cent of Australians co-signed the same statement. But feminism has always cycled in and out of public favour, with periods of protest (and progressive politics) followed by an equal and opposite backlash.

In the ’80s, an era of popular conservatism, editors of the feminist bible Ms. magazine said that even they sometimes shied away from using the F-word; in 1998 Time ran a cover story titled “Is Feminism Dead?” It would be worth interrogating whether the editors were male, and how fragile they were in their manhood, because feminism doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

Right now, marked by rising rates of male loneliness and suicide, a crisis of masculinity is unfolding. It’s a widespread challenge that benefits no-one – though nor does the lazy inclination to frame women’s liberation as the problem. Men struggle to forge close friendships? Blame feminism. The dating landscape is dire? Blame feminism. Low birth rates? Feminism, again. Manual labour jobs are declining? Those feminists!

In the aforementioned survey, 52 per cent of Australian men (and 27 per cent of women) said they believe men are being expected to do too much to support equality.

While young girls were fed images of high-flying women in power suits, boys weren’t shown aspirational models of stay-at-home dads and homemakers

And that’s really the crux of the current conversation: as gender norms shift, what is a man/woman’s role in the home (in hetero relationships) and in the workplace? Millennial and gen Z women grew up being told they could rule the world and, more than any generation before them, they came of age with the genuine option to be financially independent.

But while young girls were fed images of high-flying women in power suits, boys weren’t shown aspirational models of stay-at-home dads and homemakers, creating a gap that nobody can work out how to fill. It’s why some women are ruling out motherhood altogether, while others are choosing to return to traditional domestic roles, a subject of endless fascination, derision and debate.

Such debate doesn’t always serve us. Feminism’s current model is far from perfect – it preferences privileged voices and lacks true intersectionality – but its core purpose of achieving gender equality can get lost in over-analysis and nit-picking (read: 3421 think pieces and TikToks on whether Sabrina Carpenter’s latest album cover is degrading, subversive or just horny. And the reality that any public-facing feminist will at some point be burnt at the social media stake for getting something wrong).

A quick scan of the internet today brings up stories such as “My feminist guilt about laser hair removal” and “Am I a terrible feminist for being an Oasis superfan?” Self-reflection is noble and valuable, but it highlights how women are drowning in guilt. Imagine if men picked at themselves with the same earnest introspection. “Am I contributing to sexual violence if I listen to Drake?” “My favourite video game reinforces rigid masculine ideals … can I still play it?”

One thing for women to stop and take heart in is the fact that we have a movement. While gender gaps in nearly every metric still favour men, women unequivocally outperform men on feminism, a centuries-long fight that’s seen us rise up, change the world and improve our lives without hurting or killing anyone.

Progress may feel slow, but it’s happening. Since this magazine launched in 1995, the proportion of women in federal parliament has risen from 9.5 to 46 per cent; more than 50 per cent of university graduates across the country are now female; paid parental and domestic violence leave schemes have been introduced; ongoing reform in consent law is strengthening protections against sexual violence; and attendance at women’s sporting events, along with media coverage, has shot up from, well, zero to record-breaking.

And we did that. In the words of the great British feminist Caitlin Moran, “Feminism is at its best when it looks like freedom. When it remembers that you must never underestimate the importance of progress looking like it could, among other things, be fun.

When it’s the place where women can feel relaxed, and hopeful in their bones. When they feel so connected with each other that, sometimes, they can go up to strangers on a train at 10am on a Tuesday, happily shouting about how they have just discovered another new, brilliant thing about being a woman.”

I don’t hold anything against the women who declined to contribute to this story. The world is burning, the discourse is never-ending and the feminists deserve a break. Although really, my question only required a six- word response. We should all still be feminists.